The law of diminishing returns – how to make it work for you not against you

I love this topic because it has so much value in general. While Skills, Impact, and One Year Plan have fairly narrow application to career growth, diminishing returns is a concept that pops up all over the place. You have probably even heard of diminishing returns in other contexts, e.g., the value of additional marketing spend. What’s great about using it in a career growth context however is that it can be used in a good way or to one’s advantage. Using diminishing returns to your advantage is unique and we’re going to cover that in this post.

If you like where this is going and want to learn to grow as a professional and set yourself up with your best chance at promotion in about 12 months, check out Entry Level Escape:

- The book (at Amazon): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BCSBNQYV?ref_=cm_sw_r_cp_ud_dp_MP32SHZB4DTJCT71KAP7

- The course (at Udemy): https://www.udemy.com/course/entry-level-escape-the-course/learn/lecture/37660172#overview

Defining diminishing returns

Diminishing returns is a phenomenon where one has to put in increasing amounts of resources (time, effort, money) to realize progressively smaller incremental benefit. In other words, the first 20% of your time spent on something produces 80% of your results. The first book you read on a topic is essentially 100% new content (assuming you were totally new to the subject). The second might be half new. The third might be 30% new. Eventually you find yourself reading an entire book for a single sentence worth of new content or insight, even if each book takes the same amount of time. This applies to many areas in life; the first course is the most impactful, the first interview, the first analysis, etc.

An alternative, but much more intuitive, way to think about diminishing returns is with money. Going from an annual income of $50,000 to $150,000 is life changing, going from $5,000,000 to $5,100,000 is not. $100,000 is a lot of money in general, but to someone who already has quite a bit they won’t feel it as strongly as someone with very little.

Mapping diminishing returns to skills

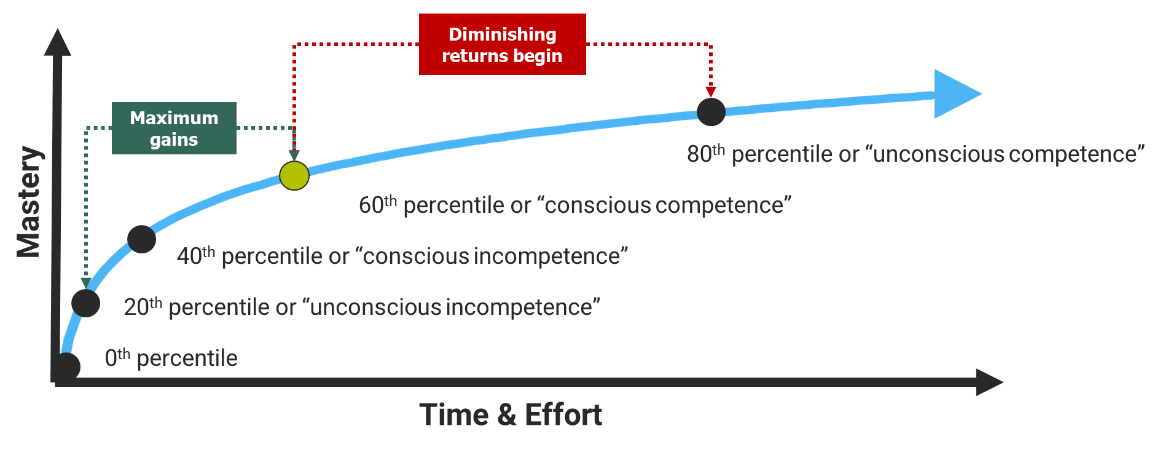

Now that you understand diminishing returns, let’s apply it to skills. First, a simple framework to understand competency level using a simple framework. The first dimension is conscious vs unconscious. Conscious means you are acting intentionally and deliberately. Unconscious means you are not, it’s more effortless or automatic. The second dimension is competence or incompetence. Competence is achieving a “good” outcome, incompetence is its opposite. With this 2 x 2 framework you get the following (I’ll use my own journey with PowerPoint to illustrate):

- Unconscious incompetence – the person doesn’t know what good looks like and isn’t really doing anything intentionally. It’s pure instinct and produces terrible results. For an example, my first PowerPoint deck ever, I basically copied a paper I wrote in Word into PowerPoint and remarked how weird it was that my boss wanted the paper chopped up into slides.

- Conscious incompetence – the person is intently working towards something but doesn’t have the mechanics or skill to deliver quality yet. This can sometimes be known as the “valley of frustration” because this is where one tries and fails. It’s hard to try and fail and then try again. I got here eventually, to my manager’s chagrin, with PowerPoint although we were averaging maybe 10 or more rounds of revisions (and in hindsight the slides were super ugly).

- Conscious competence – the person understands what good looks like and is able to deliver good results by deliberately focusing their efforts towards good. This is where one can claim they have a specific skill because they are officially above average. When I was consulting, due to sheer volume of repetition, super long nights, and targeted coaching, I was able to climb into this level. I knew I made it when the revisions got down to 2 or even the occasional 0.

- Unconscious competence – the person is able to produce “good” results without having to focus or expend any real effort. This doesn’t necessarily mean revision rate gets to 0 and stays there, it’s more a natural fit or feeling when using the skill. I consider my PowerPoint skill to be roughly at this level simply because it feels natural and I don’t burn much time or energy making good content. I got here due to continuous use but also because I started to teach it to others.

Diminishing returns sets in when one keeps going after they reach conscious competence. This is not to say that one should never keep going, there is tremendous satisfaction in mastery. The point of drawing the line is to point out where diminishing returns sets in so you can make an informed decision that progress beyond conscious competence will come at greater cost.

Below is a visualization to tie this all together for you:

Making diminishing returns work for you

As promised earlier in the blog post, you can exploit diminishing returns to grow quickly in a diverse range of skills. Here’s how to think about it – if the first few books, courses, trainings, seminars, etc., give you disproportionate new growth and knowledge and you can reach “good enough” or “conscious competence” in maybe a month or two of additional practice, then you can cycle through new skills and stay in beginner mode for a year or two to build a wide base for your career. This is the epitome of “becoming ‘good enough’ is a weekend’s work; becoming ‘great’ is a life’s work”. What’s great about consistently aiming for “good enough” is that it scales with your level. You’ll always be able to re-calibrate as you move up.

By continuously cycling what you learn you not only broaden your skill base but also avoid boredom. Imagine how difficult it will be to find the next new insight after you’ve been doing something for years. You may have to read entire books, attend entire seminars, or take entire courses just to find a single nugget. That definitely runs the risk of boredom. But, if you just pivot to a new skill then things stay fresh, this helps keep you engaged as you push forward not just in your One Year Plan (for promotion) but throughout your career.

How diminishing returns works against you

Hyper-specialization, often in your Primary Skills, is going to be your first encounter with diminishing returns. By definition, because you’ve been trained in your Primary Skills to a fairly high level, you are starting at conscious competence. You’re already above average (relative to a general population) and have the ability to deliberately work towards a good deliverable. The temptation to further specialize, to master your Primary Skills, is going to be strong for a few reasons:

- It’s going to be comfortable – these skills are familiar to you, it’s much more comfortable to get better at what you’re good at then good at what you’re bad at

- It’s natural – you already have an affinity for your Primary Skills, so your personality will draw you back towards Primary if unchecked

- It’s intuitive – if you’re a junior analyst and want to be a senior analyst then obviously you need more Primary Skills to match the senior

- It’s common – chances are your peers are falling for the Primary Skills trap, so you’ll end up doing the same to keep up with them

None of this is wrong in any sense of the phrase, but they are suboptimal if your goal is faster promotions. It might take you a full year of deliberate effort to grow your Primary Skills to a senior level and you still have to somehow grow them faster than your peers. That means even more time and even more effort to pull ahead. This is diminishing returns. Yes, mastery can lead to a fulfilling career but remember:

The best specialist in your department reports to an executive “generalist”.

If you want to climb higher, build wider with skills, and you can build your base wider faster by keeping an eye on diminishing returns and staying in the “maximum growth” zone.

Putting it all together

Now that you’re ready to exploit diminishing returns and cycle your skills learning to grow wider faster here’s how you can set yourself up for maximum success. First, figure out which Complementary Skills you want to learn. You don’t have to be exhaustive and you’re not committed to it if you realize you need or want to pivot later. The point is to give yourself some runway so you don’t lose time picking skills once the training machine gets momentum. Second, plan on how you’re going to learn (Udemy, YouTube, book, seminar, etc.). This is primarily to spot any time or budget constraints (e.g., maybe Edward Tufte’s aesthetics seminar is only available to you in February, plan around it). Third, make sure you plan for practice, ideally at work on real work. This last item is critical, you don’t have a skill until you use it. It doesn’t matter if you’ve read one book or one hundred books, no application means no skill. With curriculum in hand, go get em!

If you found this post helpful and want more ways to grow as a professional and set yourself up with your best chance at promotion in about 12 months, check out Entry Level Escape:

- The book (at Amazon): https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0BCSBNQYV?ref_=cm_sw_r_cp_ud_dp_MP32SHZB4DTJCT71KAP7

- The course (at Udemy): https://www.udemy.com/course/entry-level-escape-the-course/learn/lecture/37660172#overview